(This post is part of the 31010 Series of posts on Risks & Ventures. For more information on this series please follow this link).

[UPDATE: 30 April 2020. Please note that this post was written before the SARS-CoV-2 virus spread out of China, therefore also before the idea of “a restriction” became so closely associated with this pandemic.

The term restriction is used here in a generic way to describe risk response actions that involve limiting activities, and this article is not intended as a political commentary on the appropriateness of any particular national policy relating to the present situation.]

When I’ve been advising clients on how to mitigate their risks in certain specialist areas I have occasionally come up against two extreme attitudinal positions.

The first, and thankfully much rarer, extreme is a near-complete unwillingness to acknowledge certain types of hazards are sufficiently likely or important to be concerned about, or that ‘well in any case there isn’t much budget to do anything about that even if I wanted to’.

It’s not great to be a consultant facing an attitude this, and it’s probably worse on the occasions when you know that this person you are dealing with knows they are being deliberately obstructive, rather than doesn’t understand the situation. At least with the latter it’s easier to win some buy-in through rationally presenting evidence.

Like I said, thankfully it’s been quite rare for this to happen in my experience.

The second extreme is those customers who are so concerned about their relevant hazards and threats to their objectives that they want to continue to add more and more control and mitigation measures, to an extent that they far exceed (one, or all of) what is legally required / what is reasonable in the circumstances / what is adequately demonstrating corporate and personal due diligence / and what is a reasonable budget to set against the hazard.

I have most frequently encountered this when it has concerned worker safety issues with managers who have been genuinely motivated with the best duty of care intentions, which frankly is quite heartening to see. However, when mitigation starts to become unreasonable to the extent that is becomes too costly in time, resources and effort then not only is this not in the best interest of the company, programme or project, it can also lead to other different types of hazards.

For example if you add more, possibly unnecessary, steps to a process that makes it onerous for the workers doing it, this may have the short-term effect of controlling certain types of hazards a little more, but it also might significantly increase others corporate hazards including staff turnover once worker inertia and boredom sets in.

The other side of this idea is that if you find yourself with a difficult objective with a lot of risk, and you are pursing a strategy where you are having to do more and more mitigation to the point that it starts to feel unreasonable; whether because the mitigation becomes prohibitively expensive or just unrealistic in another way, this is also a sign that you should probably take a look at your objective and have a good think about firstly, whether it is worth it, in terms of the potential return on investment, and secondly, if there is a different strategy that you can consider adopting instead. (1)

A common example of this in Europe is the cost of insurance for young drivers in certain types of vehicles sizes of engines or price levels. A young driver might really want to drive a vehicle with a larger engine and be able to afford to buy an inexpensive older model of car but the cost of getting insurance may be so prohibitive on top of the purchase price, (even if they can get insurance at all), that this might mean postponing their objective for a few years or going with a less powerful alternative.

Likewise the insurers are looking at it from the perspective of whether accepting this business is within their own tolerable limits given the aggregate statistics that show rates of incidents involving young drivers, and setting a high price accordingly.

As we have said in some other posts, every time you add some mitigation in one area to deal with a potential hazard, you also lose something else, this ‘something else‘ might just be some of your budget but it just as easily could be process time, administrative detail, or a human factor like long-term staff buy-in.

The right amount of mitigation is always going to be the amount that is enough for the objective, not too little and not too much either.

As Low As Reasonably Practicable

ALARP or As Low As Reasonably Practicable is a solution to help find the tolerable limits of risk (2) and in IEC 31010 it’s described as a technique for evaluating the significance of risk.

ALARP is a concept that encourages people making risk-related decisions to ask themselves how much mitigation is “reasonably practicable“, and whether doing more mitigation would still be reasonable in relation to the objective that is being pursued.

If the answer starts to be no or even I’m not sure then this situation requires further review and assessment, and it might mean that the objective needs to abandoned or changed or substituted into something that can be achieved in a reasonable way.

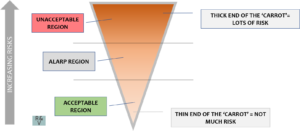

ALARP assessment is frequently used to categorize risks in three ways:

- intolerable risk, where the risk cannot be accepted unless in quite exceptional circumstances.

- broadly acceptable risk, where the risk is low enough that further mitigation isn’t necessary, although in some cases could still be implemented if reasonably practicable.

- the ALARP region, which is between intolerable and broadly acceptable, and where further mitigation is advisable if reasonably practicable.

This is called the “Carrot Diagram” and it is used to represent the idea of ALARP. The thickness of the ‘carrot’ indicates how much risk is left after mitigation, (i.e. the “residual risk”). At the thick end of the carrot there is a lot of risk and this is the intolerable area, and at the thin end there is a low risk and this broadly acceptable. In the middle of the carrot is the ALARP region where it might be acceptable or might not depending on what else can be done.

OK, but how does this really work for me?

Taking away the technical language what does this mean and how can this help me?

- There will always be stuff that you will never reasonably do. It might be sky-diving, travelling to certain places in the world or accepting a stretch corporate position that you know is going to lead to a quick burnout.

- There will always be stuff that is generally acceptable to you. Maybe flying in planes but not actually jumping out of them, travelling internationally but to nice holiday resorts, and accepting jobs that offer challenging work but with reasonable work-life expectations.

- Stuff that sits between these two positions. Perhaps like a tandem skydive, some adventure tourism as part of an organised tour, and job that could be very challenging and stressful but potentially manageable or necessary in the short-term.

All the things at 3. need a closer look, but might either verge toward intolerable or acceptable depending on what mitigation measures are possible, and whether those measures justify the end results.

So if your tandem skydive is going to be very expensive and / or only available nearby with a company whose safety record you are not happy with then it’s best to postpone. Or you might choose to take that corporate job in case 3. but then put in place some mitigation measures like specific terms and conditions in the contract like flexi-hours, or do some other things in your life to reduce the impact of the job, for example it might be reasonably practicable to move a little closer to your work place so you don’t have a tough job and a long commute as well.

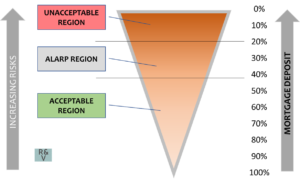

Here’s an example of the ‘carrot’ in action, concerning mortgage payments and deposits.

Let’s say a couple want to buy a new apartment and they are thinking about the level of regular payments they can afford.

They have done some calculations and reckon they can definitely pay about $850 a month or less in mortgage but would struggle to pay more than about $1150.

Between $850 and $1150 would therefore be their ALARP region, where it might be possible but they may need to take some additional mitigation measures to make it workable, like working extra shifts or cutting down on some expenses.

On a $300K value at a 3% mortgage this is what their ‘carrot’ would look like for their required deposit level. [Let’s say they already have a lot of property equity so a $300K purchase is realistic for them.]

If they only want to pay up to $850 monthly they could borrow up to about 40% LTV, but if they go up to 20% LTV this would be unacceptable as they wouldn’t be able to make their payments. Borrowing between 20% and 40% is their ALARP region.

In certain circumstances ALARP is used as legal terminology, so if you ever hear someone using it in the workplace you may need to clarify what it means, however the basic practical applications of ALARP, which are that:

- sometimes you need to ask yourself if the effort is worth the objective, and,

- you can set yourself a “zone” between the two extremes of acceptability and unacceptability on any issue, threat or objective where you recognise more careful thought is required before acting,

are two very practical and universal takeaways from the concept.

Why not have a think about it now? Think about something you definitely can’t or wouldn’t do and something that you definitely could or would. The space between these two is your ALARP zone.

(1) In cases involving workplace safety a commonly-used rule of thumb is that the costs and benefits of further mitigation need to be ‘grossly disproportionate’ for a ALARP situation to be applicable, but legislative requirements and definitions do vary country-to-country so please take professional advice if this is potentially relevant to you.

(2) This same general idea is also sometimes known as SFAIRP or So Far As Is Reasonably Practicable.

Although they broadly follow the same idea there is a little bit of technical difference between ALARP and SFAIRP, but this is one that is probably only for professional risk managers, so I’d recommend taking a look at IEC 31010 directly if you are interested in knowing more.